Cemetery Group in Uxmal

The Cemetery Group in Uxmal — like the Dovecote and North Group — is what scholars refer to as an amphitheater court, where barrier mounds frame a courtyard on three sides while the fourth side has a dominant temple platform. Typologically it is earlier than the free-standing block design of the Nunnery Quadrangle, Quadrangle of the Birds and the Governor’s Palace. While the ruins of the Cemetery Group are in a less-than-desirable state of preservation, the site holds important evidence documenting foreign trade contacts and relationships between Uxmal to Chichen Itza in the late 800s.

At the center, an amphitheater courtyard contains four platforms or alters three of which have depictions of skulls and crossbones from which the group gets its name even though no mortal remains were ever discovered there. This cluster was neither a cemetery nor a place of death but a place of vital life and likely served as a royal palace.

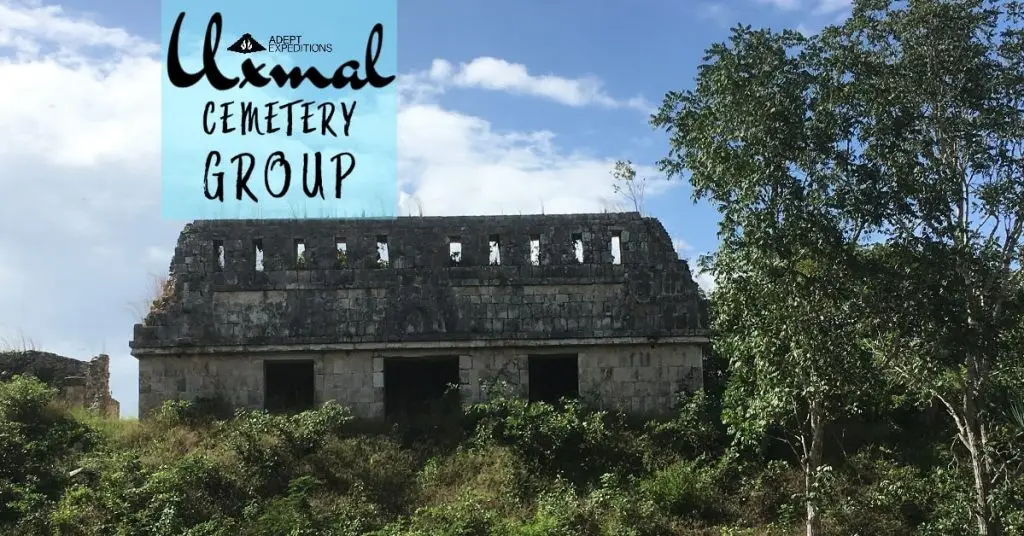

Whereas the ancient Maya had the luxury of walking up a stairway that led to a vaulted gateway giving access to the complex from the south, modern visitors have a steep incline up a rocky passage between the north and east range of ruins. The long building that once provided the principal entrance from the south is now nothing more than a massive mound of rubble buried beneath the earth in a state of ruins making it barely noticeable. To the north, a truncated pyramid-temple that without question was a mighty monument in its heyday has now been reduced to a pile of rubble overtaken by dense vegetation. Another long-range building once stood erect in the east but has since fallen.

While this group was by no means a mortal cemetery it is indeed a place where temples — once thriving with life — now rest in ruins. Most of the piles of stone and earth are often passed over by the casual, unsuspecting tourist who feast their eyes only on what is immediately visible; a medium-sized platform on the west side that once supported three single-room buildings running north to south, of which only the central building has been sufficiently preserved.

While the central building has been restored the smaller buildings on the north and south have fallen. Two of the three entrances adjacent to the central doorway were filled in with dry-laid rubble upon discovery. This could only mean that the ancient architects intended to use the temple as a substructure but for some unknown reason, the building activity ceased preventing further construction from occurring. Stone tenons project from the roof comb indicates an earlier presence of stucco sculptures while crest work similar to the Dovecote give the otherwise sober building some character.

While the architectural and decorative features are signs of an earlier Puuc style, the stonework and construction techniques are characteristic of the Late Puuc style suggesting that this building was either constructed during a transitional period or built later perhaps paying homage to a more ancient style. Evidence from the hieroglyphic platforms located in the courtyard supports a date between 850-880 AD. In a traditional Maya three-part building scheme, the long central temple is flanked by two apartments and though they are physically separated by a narrow passageway, they are tightly linked compositionally. The passageway evokes the concept of the vaulted passage dividing the Governor’s Palace which may have been a response to this early model prototype.

Perhaps what is most interesting for our study is how the temple’s triptych doorway aligns perfectly with an unusual stone with three circular holes across the court on the east side. The only thing between them is one of the four sculpted platforms. Three of the sculpted platforms form a row on the north side of the courtyard, near the base of the truncated pyramid, while the fourth is found near the center of the court, roughly centered on the central doorway of the triptych temple on the west side.

Sculpted motifs of skull and crossbones bear a striking resemblance to the symbolism used in Freemasonry. Some Freemasons, such as Augustus Le Plongeon was convinced that the roots of Freemasonry were to be found in the ancient Maya culture. However, the motifs are uncommon for Puuc art and architecture. The platforms precede 897 AD, the traditional date associated with the Toltec conquest of Chichen Itza so the foreign symbols are best understood as influence from Chontal Maya traders or Putun Itza Maya who, with their Mexican connections, had ruled Chichen Itza since the middle 800s. These symbols serve to document evidence of such trade contacts.

The platforms may have been used as Tzompantli to public display human skulls. While crossbones is often attributed to death in the western world, the femur bone is where the red corpuscles are stored thus a symbol of vital life force for the Maya who viewed bones as seeds. On one of the corners a skull is depicted upside down. Was this a representation of the underworld? We can’t be certain but it’s reasonable to conjecture. The upper register of the northwest corner of one of the platforms includes the glyphic name for “Lady Kuk”, mother of Kakupacal of Chichen Itza, which implies a relationship between the two great temple-cities.

Symbolist Interpretation of the Cemetery Group In Uxmal

Since there are three doorways on the central structure of three temples in the Cemetery Group in Uxmal sharing an alignment to an unusual stone with three circular holes, how can we see if they are related? The three circular holes in the stone are obviously conveying a symbolic significance.

Three was a ubiquitous and sacred number for the ancient Maya, as it not only represented life, death and rebirth, but it also symbolized the three bright stars — which they called the ‘three stones of the heart’ in the southern part of the Orion constellation and represented by three large stones that form the fireplace in traditional Maya homes. I suspect the stone was used as some sort of observation device and may hint at a ley-line perhaps marking a strong concentration of subtle earth energies.

During our esoteric symbolist study tours of the Yucatan, we provide rods, brief instruction, and then give guests a go at dowsing in this area. Year-after-year we produce similar results where about 8 out of 10 of the guests experience a significant change in the dowsing rods as they cross the threshold between the centers of the stone and the triptych temple.

Location

Located about 160 meters (524 feet) west, and slightly south of the Nunnery Quadrangle, the Cemetery Group is somewhat off the beaten path and most tourists don’t make it this far.

Like the nearby Stelae Platform, it gets very little tourist traffic, and there is always a very special atmosphere surrounding any of the Maya ruins when no one else is around. This in itself justifies a visit to less popular or more inaccessible sites. While the name would suggest a heavy and curiously unsettling atmosphere, many people feel a peaceful and tranquility, both within and without. It’s impossible to say why.